Practical solutions for real-world problems

Data access

A key contribution of the IBDT is to develop policies and platforms that facilitate and enable the access provision of building data. A portal for UofT building data will serve as a testbed for use by partner organizations. The portal will allow easy access to students and researchers. The data within our portal will include:

- Structured data such as sensor data, utility data (e.g., electricity)

- Unstructured data such as building layouts, reports, and other documents

At the core of IBDT mission is to assure open, flexible, yet secure sharing of facility data. This includes three objectives:

- Understanding data: identifying and profiling data to be shared, including, for example, who will need what data, for what reason; what are the inherent risks of sharing specific datasets; existing and desired data quality and update rates; metadata; and data structures.

-

Profiling users: describing potential users, including, for example, their needs: data formats, frequency of use; their relation to UofT; the match between their needs and their data use capabilities: how can we support a more meaningful and equitable use not just access of data.

-

Modeling usage: rationale and nature for data use, including, for example, access modalities (view vs. download); duration (and expiration) of usage rights; sharing/re-publishing regulations; and, most importantly, monitor usage patterns and irregularities.

While traditional access management “reacts” to user needs and provides them with “raw” data, at IBDT we aim to take data access to the next level, where access services provide additional value in three ways:

- Data modeling: asset data is notoriously fragmented and lack interoperability. In fact, most of data, for example, layout and activity/schedule data, are informal. This hinders the use of many analytics tools. IBDT will use best practices in data modeling and linked data systems to formalize a suitable means to harmonize data structures, when appropriate. For example, creating a taxonomy of building spaces based on their functions and operational attributes; the use of BIM to capture the physical aspects of buildings. Combining these two services, researchers will be able to inquire about, for example, the patterns of classroom usage in summer session vs. winter session; energy consumption levels in labs while unoccupied; level of crowdedness in hallways after lectures. Such advanced searches can be insightful to asset management.

- Data analytics: instead of providing raw data, IBDT will compile and regularly share analytics of data. This can span a spectrum from simple patterns in data (see above) to predictive models (e.g., prediction of next work orders or the cost of a work order) to basic simulations of possible futures.

- Access policies: examine best practices and options to advise UofT on the next phases of data sharing and access management protocols, including synthesis of data usage patterns, analysis of user feedback, and benchmarking changes in public policies. Basically, update this governance plan through i) bottom-up learning from actual usage and input from users, and ii) top-down synthesis of advances in research work and progress in data policy making.

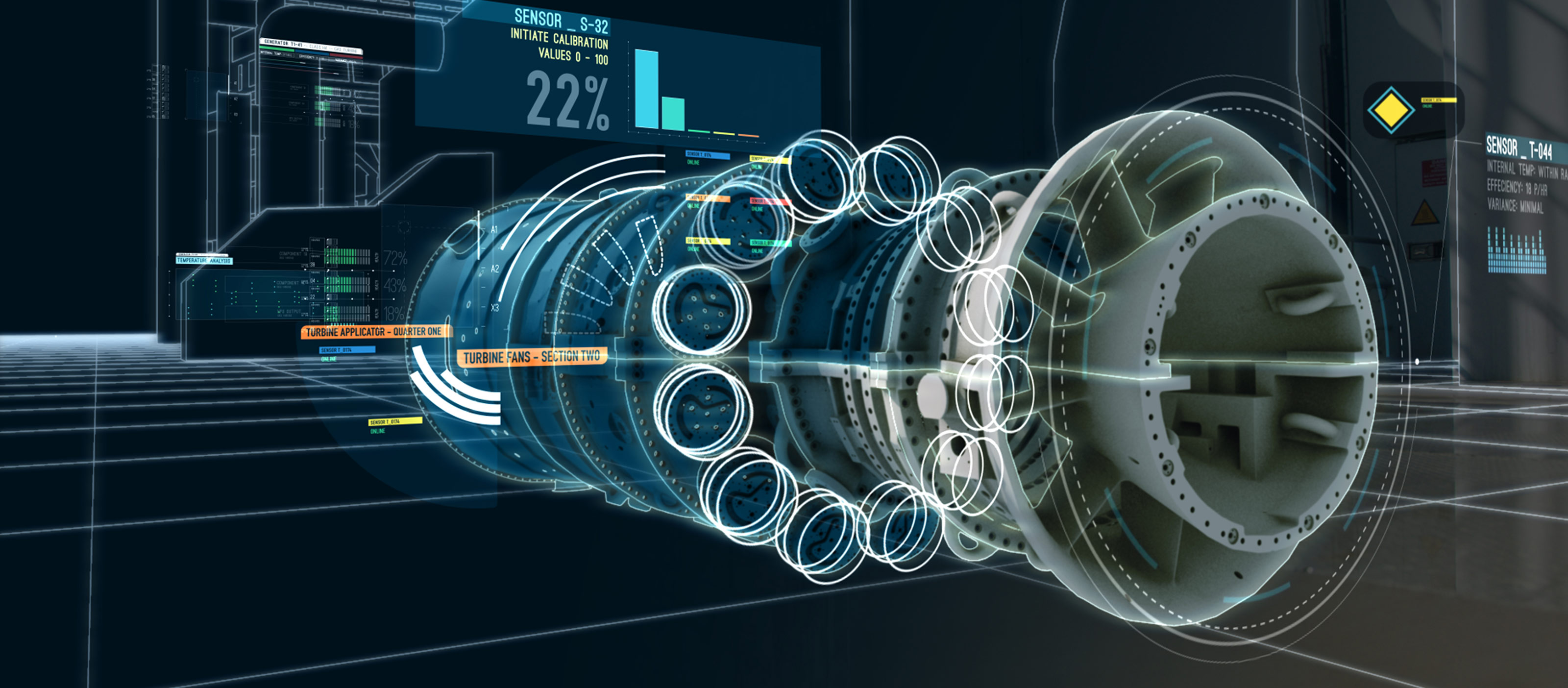

Digitization

While developing BIM (Building Information Modeling) models for UofT buildings is not the objective of the IBDT, the Center will showcase best practices in digitizing existing building layout data and linking that to IoT (Internet of Things) data. The experience gained in creating building information models for UofT buildings will be used to help partner organizations develop BIM strategies for their own facilities.

Empowerment by Knowledge Democratization

At IBDT, our central ethos is rooted in the democratization of knowledge. We envision a harmonious intersection of professional expertise and user curiosity, manifested in an expansive, empowering platform - a dynamic and engaging ecosystem of knowledge.

Our philosophy of empowerment is imbued with the spirit of play; it's an arena where experienced professionals and curious users come together, exchanging information and collaboratively devising solutions. Through the intelligent application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the principles of serious gaming, we transform complex, often intimidating knowledge into accessible, easy-to-understand formats. Our framework not only invigorates engagement, but also stimulates curiosity and enriches the learning experience, fostering a vibrant cycle of knowledge acquisition, contextualization, and system appraisal.

This innovative methodology, an intersection of AI and serious gaming, represents a key strategy we are implementing to confront the threats of climate change. We are pioneering a Knowledge Graph-based system for the efficient, impartial gathering of the most current knowledge. This knowledge is then transformed into a contextually rich ontology, resonating with community engagement and learning, and sparking participation and contributions from all users.

Complementing this, we utilize the capabilities of advanced AI large language models, such as GPT, to extract, interpret, and apply context to the amassed knowledge. This enables an iterative process of cross-validation and cross-training between the systems, ensuring a degree of reliability and effectiveness that sets a new standard in the field.

Our system is dynamic and continuously evolving. We are committed to ceaselessly refining its capacity to inspire community involvement, to improve user satisfaction, and to create fertile ground for knowledge co-creation. In doing so, we empower communities, guiding the way for sustainable and resilient development practices that effectively counter the impacts of climate change.

Linking structured and unstructured data (the graph is the new BIM)

Building Information Modeling (BIM) has played a central role in structured data management in the built industry, covering data sources from design details to IoT devices. However, the majority of data generated in this industry is unstructured, such as inspection records, work orders, discussions, and communication logs. Unstructured data contains valuable tacit knowledge from project stakeholders and is directly related to the specific needs of each project. Therefore, any meaningful digital twinning must triangulate these two datasets.

Specifically, it is important to link BIM data models (IFC) to text mining. In this initiative, we are exploring methods that utilize graph theory to achieve this linkage. We are examining the re-representation of the hierarchical schema of IFC in the form of a network. At the same time, text from bsDD is presented in the form of semantic networks. In each network, clusters of connected nodes are detected, and a link is created between corresponding clusters in both networks. This way, IFC classes are annotated with related text from bsDD, and concepts from bsDD text provide semantic depth to IFC. Additionally, project documents and reports will also be transferred into concept networks.

By matching clusters from document networks and bsDD networks, we can create a link between project document concepts and IFC, with bsDD acting as a mediatory layer (network). This approach is dynamic, as project documents evolve, their concept networks change, and the links to IFC are updated. This avoids the rigidity of typical linkage between IFC and unstructured data sources, which is usually done through mapping both IFC concepts and text keywords to a static classification system or an ontology. This unsupervised approach learns from project stakeholders to build mappings that reflect their knowledge and project conditions.

Work Order Analytics

Institutional buildings generate a significant number of work orders. For example, the University of Toronto Facilities and Services Department processes tens of thousands of work orders each year. Networks of connected work orders (and their related BIM objects) will be analyzed for patterns using machine learning to help predict the cost and duration of future work orders. Equally important, the analysis will investigate the prediction of time-to-repair and time-between-repair for key building components.

However, more important than developing predictions is to develop means to enhance the efficiency of the asset management program. The decision to fund or not fund a specific action for a building (or a set of BIM objects within a building) is reflected in the frequency and intensity of work orders.

Patterns found in work orders can then be a means to study 'decision signatures': what happens when we invest in a specific project? What is the Return on Investment (ROI) (i.e., performance gains) associated with a project?

To better understand the link between investments and gains in ROI, we will use machine learning to analyze structured data (such as cost and duration data) and Transformers to analyze text of work orders and other reports, as well as social network analysis to profile stakeholders (who is engaged in what task). Graph-based neural networks will then be used for profiling the relationship between project decisions and work orders on three levels: node level (e.g., predicting the post-decision performance of an asset), edge level (e.g., inter-dependency between work orders), and graph level (e.g., holistic contrasting of projects). We can learn what work order issues are typically associated with specific BIM objects or decision-making tasks, what (localized) operational features relate to increased frequency or intensity of work orders, and what patterns in stakeholder relationships (teaming) are associated with conflicts or their resolution.

Business Process Analysis

The process of making operational business decisions is highly complex due to the dynamic relationships between parameters, diverse perspectives about priorities, and conflicting objectives. Inefficiencies in the process can lead to suboptimal decisions, missing out on options that could have the greatest ROI. Business process models (BPM) will capture the business logic in the practice of the Facilities & Services Department at UofT. The main objective is to map operational data in different business processes by establishing a link between data models and business models. This is an essential step in reengineering business processes to be data-driven, rather than based on functional silos.

By modeling tasks and profiling their data signature, we can understand which of the predictive models (or outcomes of machine learning and data analytics) are relevant to which task. This way, as decision-makers progress in authoring a project or making changes to operational schemes, they will be served with meaningful and timely business intelligence insights.

Interactive Authoring Environment

The goal is to create an occupant-led option authoring environment in the form of integrated co-editable documents and BIM models. Occupants will be able to interactively develop and discuss goals and design ideas. As they debate, semantic network analysis will be used to capture key issues, especially ones they struggle with. Advising them on these issues requires harnessing complex, evolving (even contested) knowledge. Can we help them use web material in a streamlined process? Can we synthesize this milieu of knowledge and use it to annotate BIM objects with 'what we know'?

To distill and serve knowledge to users, we will use knowledge graphs. Unlike ontology (a top-down model of a domain) and semantic networks (key terms extracted from user discourse), knowledge graphs harmonize knowledge from diverse (web) sources into a network of concepts and supports reasoning/intelligent queries. Knowledge graphs will be used to serve climate knowledge (e.g., facts, estimates, best practices) to operators/occupants as they author options.

Users can find answers to the following questions:

- What climate: expected change in climate elements such as temperature, precipitation, and storms?

- What impacts: should migration associated with climate change be considered?

-

In what way: the link between hazards and performance, which has three challenges:

- Existence of relation: not every asset is sensitive to each climate hazard.

- Inter-hazard interaction: how to consider the interplay between different climate hazards.

- Relationship formula: how to quantify hazard impacts on asset performance.

- How much: delta costs associated with the positive/negative change in hazards.

Overall, this approach will enable occupants to make informed decisions based on knowledge of the impact of their design choices on climate change.

Generative Digital Twinning

To break the lock of normative thinking and the limitations of current practices, we need disruptive, but rational new approaches to imagine new futures for buildings. We will build a computer-assisted platform for option generation using Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) to create “generative” DT (i.e., Generative Digital Twinning): digital twins that generate and explore possible permutations of potential solutions. Students will study four dimensions of generative DT: the authoring schema, the rules, the method of creating alternatives, and the means for selecting the desired outcome.

Five key contributions are targeted:

- Generate new Business Process Models (BPM): who can do what, when, and how (based on what guidelines)? The aim is to put occupants at the center of the process and sustainability as core criteria.

- Utilize patterns from user-generated solutions to guide GAN. Knowledge is situated. GAN should be built to recognize the profile of decision-makers - what are their values, needs, and problems.

- Feed project-work order relationship patterns. Generative DT should be built to learn from reality: what worked in previous projects / what did not.

- Instead of using generic rules, examine the extraction of rules based on an analysis of semantic-social networks (concept-to-concept-to-actor clusters).

- Support automated decision-making: use “decisioning” knowledge graphs to build option recommender systems. Unlike “actioning” knowledge graphs which aim to synthesize knowledge, decisioning knowledge graphs use machine learning to capture decision patterns to help evaluate/maximize ROI.

This approach will enable us to generate new and innovative solutions for buildings, putting occupants at the center of the process and sustainability as a core criterion. By utilizing patterns from user-generated solutions and feeding project-work order relationship patterns, we can learn from previous projects and avoid conflicts. Additionally, by examining the extraction of rules from analyzing the semantic-social networks of the users and supporting automated decision-making, we can maximize ROI and make informed decisions based on a comprehensive understanding of the impact of our design choices.